The book of Psalms is not only—as Martin Luther puts it:—“a little Bible, and the summary of the Old Testament”; it is, we may say, the heart of the whole Bible. As a book of praise, it provides God’s people throughout the ages with the most magnificent sonnets of praise and thanksgiving befitting the God Almighty, the Creator of Heaven and Earth. On the other hand, as a balm for the weary, it plumbs the depths of human emotion and provides the truly penitent with some of the deepest expressions of sorrow and grief. For this reason, among others, it is perhaps the most beloved and most well-read portion of the Bible throughout the history of the Christian Church.

But more than being a book that meets the spiritual and expressive needs of the individual Christian in whatever situation he finds himself, the book of Psalms is also eminently Christological. It will certainly not do to see the Psalms as being messianic in only a few notable cases, such as Psalms 2, 22 and 110. These are indeed noted for being messianic because they are referred to by Christ and His disciples to describe the experiences and emotions of Christ during His earthly ministry (e.g., Mt 27:46; Mt 22:41–46; Acts 2:28; Heb 1:5; 2:8; etc.). However, none of these psalms are expressly prophetic if they are read without the analogy of the New Testament. Rather, almost without exception, they describe real experiences and emotions of the psalmists—especially of David, “the sweet psalmist of Israel” (2 Sam 23:1). The reason Christ could appeal to the Psalms as referring to Him (Lk 24:44) is because the psalmists wrote not merely out of the exuberance of their own hearts, but through the Spirit of Christ dwelling in them (see 2 Samuel 23:2; 1 Peter 1:11). Thus the “I” in the psalms points ultimately to the Greater David, who is both the singer (Heb 2:12) as well as the focus of the psalms.

For this reason, the book of Psalms has not only been affectionately read, but has throughout the ages been the only inspired hymnbook of the New Testament Church. Just as the Jews, no doubt, used them in temple and synagogue worship, the early Christians sang or chanted the psalms in their worship. Although the evidences from the apostolic churches are not conclusive, many commentators believe that when Paul refers to psalms, hymns and spiritual songs in Colossians 3:16 and Ephesians 5:19, he is actually referring to the Psalms only! This is because the Greek translation (Septuagint) of the Psalms, which the Apostles used extensively, identifies the psalms with all these three terms in the psalm titles. In 67 of the titles, the word “psalm” occurs; in 6, the word “hymn” is used; while in 35, “song” appears. Moreover, in 12, “psalm” and “song” are used while in 2, “psalm” and “hymn” are used. Furthermore, the Septuagint of Psalm 76 uses all three terms in its title: Eis to telos, en humois, psalmos tô Asaph, ôdê pros ton Assusion. Literally translated this reads: “For the end, among the Hymns, A Psalm for Asaph; a Song for the Assyrian.” Even without a knowledge of Greek, it is not difficult to see that the three terms were the same used by the Apostle Paul in Colossians 3:16 (psalmois, humois, ôdais pneumatikais; cf. Eph 5:19). The different endings of the words reflect the different cases in which they are used. Paul adds that these psalms, hymns and songs are “spiritual” (pneumatikais) simply because they are Spirit-inspired or Spirit-given (e.g., Romans 1:11). Besides that, hardly anyone doubt that the hymns that Jesus sang with His disciples at the Last Supper were from part of the Psalter, which the Jews called the Egyptian Hallel (Psalms 113–118).

With this in mind, and based on the principle that whatsoever is not sanctioned in the Scripture is forbidden in the worship of God (the Regulative Principle), Calvin, at the time of the Reformation, developed the Genevan Psalter (singable translation of the Psalms), with Theordore Beza and Clement Marot providing the poetic versification and Louis Bourgeois supplying the melodies.

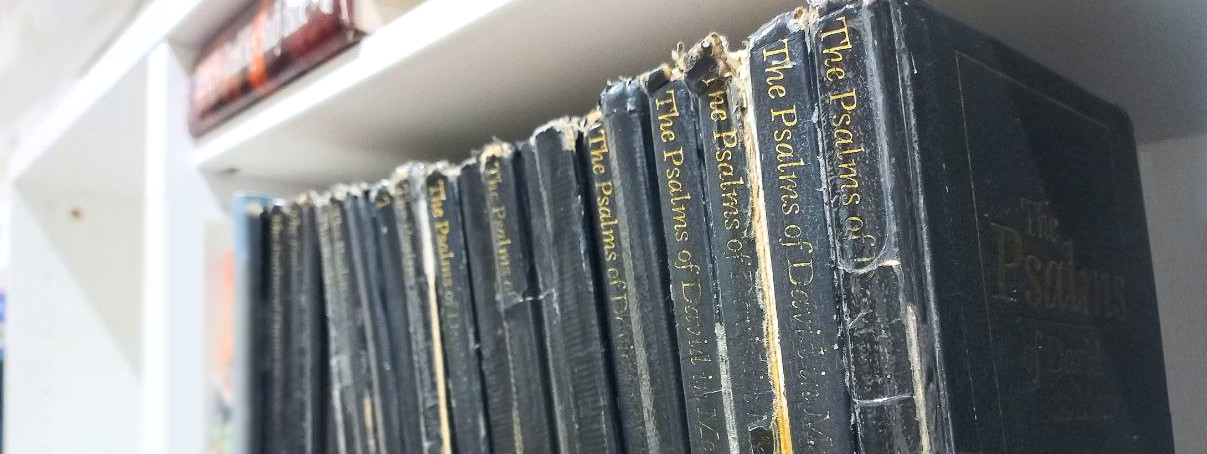

Accordingly, John Knox and the Puritans, being the spiritual descendants of Calvin, also sang Psalms only in public and private worship. This regulation is clearly reflected in the Westminster Confession of Faith, which makes no mention of hymns and songs but refers to “singing of psalms with grace in the heart” (WCF 21.5). A.A. Hodge suggests that hymns may be considered “musically-uttered prayers” and so may be regulated under WCF 21.3 rather than 21.5. However, it is an undisputed fact that the Westminster divines sanctioned only psalm-singing: “It is the duty of Christians to praise God publickly, by the singing of psalms together in the congregation and also privately in the family” (Directory of Public Worship). In fact, the Scottish Psalter, which we use in our church, is actually an edition of the metrical (singable) Psalms written by a Mr. Francis Rouse. This was presented to the Westminster Assembly and, after careful study and amendments by the three committees over a period of two months, was approved by the Assembly for use in public worship on 14 November 1645 (see Minutes, pp. 131, 163). After this, it was subjected to six years of scrutiny and revision by two different groups of highly learned and devout leaders of the Scottish Presbyterian Church. Literally, every word and phrase was carefully weighed for faithfulness to the original Hebrew texts. The result is the text as we have here. Thus we can be very sure that when we sing the Psalms in this version, we are singing the Word of God.

The issue of whether uninspired, though scriptural, hymns and songs should be allowed in public worship is more complicated than can be treated in this short introduction. However, it suffices us to realise that it is to our own disadvantage and detriment to cast aside our historical and confessional roots and to abandon the singing of Psalms altogether, or to give it the lowest priority in our worship. Calvin, standing on Augustine, was surely right when he said:

… that which St. Augustine has said is true, that no one is able to sing things worthy of God except that which he has received from him. Therefore, when we have looked thoroughly, and search here and there, we shall not find better songs nor more fitting for the purpose, than the Psalms of David, which the Holy Spirit spoke and made through him. And moreover, when we sing them, we are certain that God puts in our mouths these, as if himself were singing in us to exalt his glory (Preface to the Genevan Psalter).

Furthermore, if we would not sing the Psalms at all, for whatever reasons, then we would be in danger of “will worship” (Col 2:23), seeing we would neither follow our Lord’s example nor obey the Apostle’s injunction—which clearly includes psalm-singing, whatever “hymns” and “songs” may mean. Let us therefore endeavour, with the Lord’s help, to bring the inspired Psalms back into prominence in our worship of God, both publicly and privately (Jer 6:16!). Let us learn to sing the Psalms,—“the word of Christ”—with grace in our hearts (Col 3:16), and so learn Christ through His Psalms.

This re-production of the Psalter is designed to promote and restore the singing of Psalms in our families and, God willing, in other churches as well. Most of the Psalms in the Palter are set to the Common 8.6.8.6 Metre, which means that there are 8 syllables on the first line and 6 on the second, and so on. Any tune that can be fitted to such a metre is known as a Common Metre tune. For example, the first stanza of Psalm 103 reads:

O thou my soul, bless God the Lord; (8 syllables)

and all that in me is (6 syllables)

Be stirred up his holy name (8 syllables)

to magnify and bless. (6 syllables)

Try singing it to “Amazing Grace” or any of the popular Common Metre tunes. Try it in your personal devotion, in your family worship or in church. With some perseverance you will soon find it much more meaningful to sing these inspired words of God than uninspired compositions, no matter how romantic or inspiring they may be. May the praise of His saints redound to the glory of God through these words that He has Himself ordained for His own praise.